As the 2015 election approaches the Coalition and the Labour party differences on fiscal policy appear to be ones of emphasis – how quickly and what to cut, says John Weeks, Professor Emeritus at SOAS, University of London.

As the 2015 election approaches the Coalition and the Labour party differences on fiscal policy appear to be ones of emphasis – how quickly and what to cut, says John Weeks, Professor Emeritus at SOAS, University of London.

In the debates preceding the election of May 2010, Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown explicitly rejected public budget cuts because they would, in his view, make the recession worse. Nick Clegg, the leader of the Liberal Democrats, had in March 2010 attacked budget cutting as ‘economic masochism’. He maintained this position during the debates.

Only the Conservative David Cameron pledged his party to cut expenditure, though ambiguous about how much. The lack of a Conservative majority in the subsequent voting led to a coalition with the Liberal Democrats. Given Clegg’s pre-election opposition to any but minor cuts, the Coalition seemed unlikely to embark on radical reductions in spending. However, the leader of the Liberal Democrats reversed himself.

Suddenly, the British public discovered that its votes had produced a government dedicated to radical reduction in public expenditure. The Coalition government, and especially its Chancellor George Osborne, presented the need for expenditure reduction as self-evident. The public budget manifested a deficit, expenditure over revenue, of 10 per cent of gross national product, allegedly unprecedented during peacetime.

He avoided mentioning that the deficit excluding investment – current expenditure balance – was higher under the John Major government in 1994 (minus 9.1 per cent of GDP compared to 8 per cent in 2010). How to measure – and mismeasure – all aspects of the government budget would prove central to selling austerity policies to the British public (Weeks 2014).

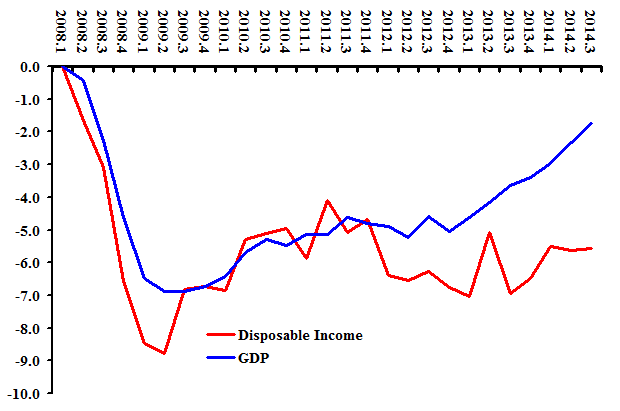

One consequence of the misguided and unsuccessful attempt to reduce rapidly the deficit is shown in the chart below. After four years of Coalition government, GDP per capita and household income per capita remain below their level when the recession hit in 2008, the slowest economic recovery on record.

GDP and household disposable income, percentage difference from 2008 Q1

As the 2015 election approaches the Coalition and the Labour party differences on fiscal policy appear be ones of emphasis – how quickly and what to cut. In his speech to the Fabian Society on 25 January 2014, shadow chancellor Ed Balls committed Labour to surplus on current expenditures. In practice this would imply an overall deficit of about 3 per cent of GDP. In contrast, the Chancellor seeks an overall surplus.

In 2010 British voters faced an election in which one of the three major parties supported fiscal cuts – austerity – and two did not. The austerity party, the Conservatives, received 36 per cent of the votes cast, while Labour and the Liberal Democrats combined for 52 per cent. None-the-less, a few weeks after the election austerity became the economic policy of the new British government.

Unless a change occurs in party positions in 2015, voters will find on their ballots no major party opposed in principle to continuing economic austerity for the foreseeable future. The rise of the Green Party in the polls does offer many voters a clear anti-austerity position. Of the parties with prospects of wining seats at the national level only the Greens recognise that austerity is bad economics and worse social policy, divisive because it generates poverty and inequality.

John Weeks is one for the founding members of Economists for Rational Economic Policies, a group dedicated to fostering serious debate over economic issues during and after the election campaign. Follow him on twitter, #johnweeks41