By Dejan Djokić

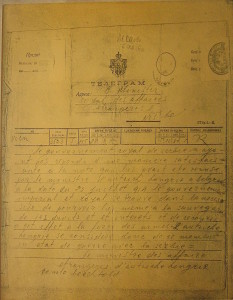

The Austro-Hungarian government’s declaration of war in a telegram sent to the government of Serbia on 28 July 1914, signed by Imperial Foreign Minister Count Leopold Berchtold (wikipedia)

Squeezed between the centenaries of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess Sophie in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 – which inspired a recent media frenzy, numerous academic conferences and even political events – and the Great Powers’ entry into the war in early August, almost forgotten is the date on which the First World War actually broke out: 28 July 1914, when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia.

The 1878 occupation and the 1908 annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina by Austria-Hungary were the main, though not the only reasons for tensions between Serbia and the Empire. Belgrade’s efforts to escape Habsburg domination led to Vienna imposing a trade embargo on Serbia in 1906. That same year a Croat-Serb Coalition won elections in Croatia (then part of Austria-Hungary), campaigning for the South Slavs’ self-determination. Serbia and Montenegro – the only two independent Slav states, Bulgaria and Russia aside – significantly increased their territory as a result of the 1912-13 Balkan Wars, while Belgrade became a regional political and cultural centre.

The Ottoman defeats against Italy (in north Africa) and the Balkan states in 1911-13 and an internal crisis caused by the Young Turks, influenced the Habsburg perception of a threat posed by its Slavs and neighbouring Serbia. The potential risk to Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, a visit arranged on the occasion of Habsburg military manoeuvres, was clear to many. The Kosovo Battle, fought on 28 June 1389 between a Serbia-led Christian coalition and an Ottoman army which included Christian vassals, had turned into the symbol of the Serbs’ and Yugoslavs’ suffering and struggle for independence.

Gavrilo Princip and other Young Bosnians were Yugoslav nationalists and their ideology should be understood in a transnational context of European national movements. They read widely and were inspired by the Giovine Italia, Junges Deutschland, Russian anarchists and social-revolutionaries and west European socialists and utopian thinkers. Aspiring philosophers, poets and writers – they included Ivo Andrić, the only Yugoslav Nobel prize-winning writer – the Young Bosnians believed their goals were noble, means justified, and that Serbia was a Yugoslav Piedmont.

Belgrade condemned and distanced itself from the assassins, but Vienna blamed the assassination on Serbia and Serb nationalism. The Serbian government was not implicated. In early June prime minister Pašić acquired knowledge of armed Bosnian students crossing the border and tried, unsuccessfully, to prevent them. Princip and others were aided by the ‘Black Hand’, a nationalist organisation which believed that murdering ‘tyrannical’ Habsburg rulers was justified, and which was in conflict with Serbia’s leadership.

Having secured Germany’s support, Austria-Hungary issued an ultimatum, designed to be rejected, to Serbia on 23 July. Five days later it declared war on Belgrade, by telegram, in French. By 1918 the Dual Monarchy disintegrated; Serbia survived, becoming the core of Yugoslavia.

The war of interpretations of the war’s origins continues 100 years on. Centenary-inspired, sometimes unoriginal, post-Yugoslav, Habsburgophile/Serbophile interpretations notwithstanding, the ongoing debate testifies to the significance and relevance of this complex subject – for students of history and related disciplines and wider public alike.

Dejan Djokić is Reader in History and Director of the Centre for the Study of the Balkans at Goldsmiths, University of London, and Co-convener of the Rethinking Modern Europe seminar at the Institute of Historical Research. He is currently working on A Concise History of Serbia for Cambridge.