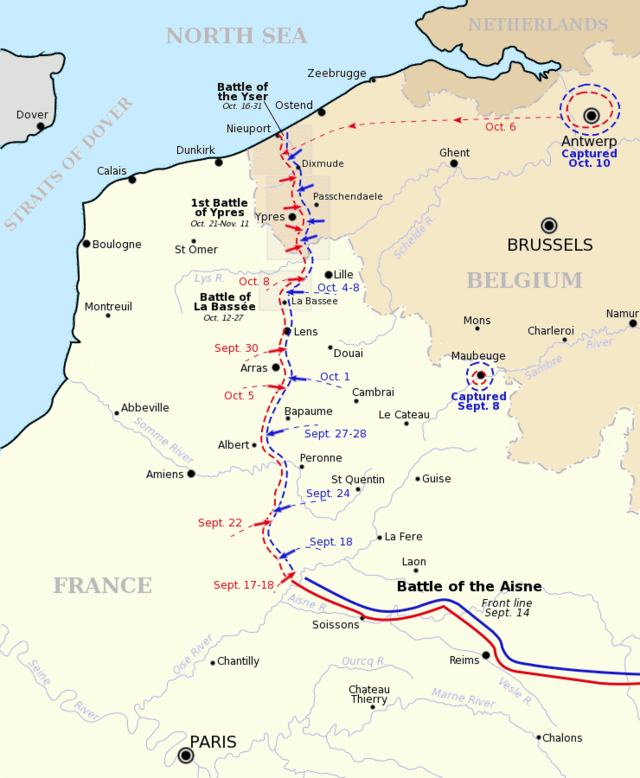

In October 1914 the British army found itself fighting near a Belgian town that was to become synonymous with British military experience in the First World War, Ypres. While traditional images of individual and collective heroism worthy of pre-industrialised wars have ever after been associated with the First Battle of Ypres, which raged from early October until mid-November, in fact the remnants of the British regular and Indian armies were embroiled in a very different sort of battle.

Battalions were shuffled in and out of ‘the line’, decimated and then relieved, as an entrenched defensive front was formed to oppose repeated German efforts to break through to the Channel Ports. This would be the first prolonged battle of attrition, a prototype of the costly but localised fights that would characterise warfare on the western front until 1917. The fact that modern armies deployed hundreds of thousands of men in limited space and could replace losses with trained reserves meant that a single battle, however huge, would not decide this war.

It was the German army that demonstrated the futility of trying to use flesh and blood alone to break fortified defensive lines, most notoriously in the subsequently mythologised ‘Kindermord’ at Langemarck of 21–24 October, when raw volunteers were thrown en masse against the French and British defences.

In 1914 the defenders lacked the artillery and machine gun firepower of later years, but rifle fire alone was sufficient to stop such ‘human wave’ attacks in their tracks. Armies took to trenches for protection in the calamitous campaign of autumn 1914, the most costly of the war, presenting military leaders with a new military problem, how to attack on a fortified, firepower-dominated battlefield. It did not take long to realise the solution was to fight fire with fire, but it took time to reequip and retrain armies to do so.

It is no coincidence that the French general who directed the defence of Ypres in 1914, Ferdinand Foch, would emerge as the supreme military leader and theorist on the Allied side. He learnt in autumn 1914 that human lives should be used sparingly, and that firepower determined what was and was not possible on the battlefield. But the factors of mass armies, restricted space for manoeuvre and the increasing industrialisation of the battlefield that had appeared by 1914 would not go away. Foch and others adapted armies and methods to the realities of warfare, sometimes painfully but increasingly effectively. By the time the Allied armies Foch led in 1918 finally drove the Germans out of France warfare had modernised; but many of its novel elements were present in the indecisive fight for Ypres in 1914 that confirmed the stalemate of the ‘front’, while initiating the most rapid and fundamental change in the nature of warfare that the world has seen.

William Philpott is Professor of the History of Warfare in the Department of War Studies, King’s College London. He is specialist in the history of the First World War and of Anglo-French relations. He is the author of Attrition: Fighting the First World War and Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice on the Somme.