By Dina Gusejnova

Familiar images from 1989 show people on the Berlin Wall, dancing, holding hands, feet dangling east and west, and laughing. Twenty-five years on, these images remain icons of a fleeting phenomenon: political happiness.

It is all too easy to confuse the end of this particular story with the end of history. Injustice can exist without visible walls. How emblematic has the fall of the wall really been when it comes to the 20th century?

Actually, it is the 19th century and not the twentieth that had first beaconed an era of tumbling walls. Back in 1848, Marx and Engels spoke of the bourgeoisie breaking down ‘Chinese walls’ through the forces of capitalism. But it was in Europe, from Lucca in the south to Vienna in the centre and York in the north, where medieval fortresses and walls of early modern city-states first gave way to fashionable promenades. Like these, the Chinese wall never had to be destroyed in order to change its significance: it was simply absorbed into a new empire and, by the end of the 19th century, turned into a tourist destination, intact.

However, by the late 20th century, Europeans, far from seeing more walls wither away, engaged in the construction of new walls of barbed wire, concrete, and steel, which continue to divide cities such as Nicosia, Belfast, and Jerusalem. Numerous other frontiers, invisible to most of us, policed by the European international border task-force, Frontex, protect fortress Europe in its borderlands reaching from Poland to Greece and Morocco.

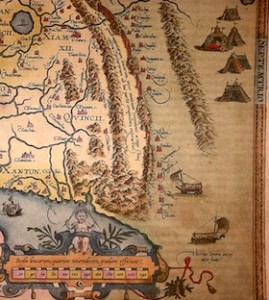

Detail of the map of China engraved by Abraham Ortelius (1584), the first map of China printed in a European atlas (Wikipedia)

How long does political happiness last and where are its new boundaries, once a wall like the one in Berlin has tumbled? Franz Kafka’s parable about the construction of the Great Wall of China offers some clues. In this story, which he wrote in 1917, as the empire of which he was a subject was in its death throes, Kafka projected himself into the mind of a construction worker. Looking back, Kafka’s worker was puzzled about two things. Why is it, he asks, that the Great Wall was built in separate segments, leaving so many gaps between them? Then there was another paradox.

According to the emperor’s loyal Mandarins, the wall was needed for protection against encroachments by the Northern tribes. But believing in this threat required trust: the worker himself had never seen anyone from these tribes approaching their territory. In fact, he could not be sure that such tribes existed at all.

His lingering suspicion was that perhaps the wall’s primary function was the process of building itself – i.e. the recruitment, training and intraimperial migration of the workforce? As soon as the gaps between the wall’s segments were filled, that particular empire began to crumble.

The moral also applies to the process of deconstruction. As long as there was still work to do in breaking it down, it had a meaning and a function for those who chose to identify with this particular instance of happiness. For example, by travelling to Berlin or buying ever smaller souvenir pieces of the wall at the airport.

In 2014, Berliners are struggling to preserve a last piece of the wall against developers of real estate. Now we know: this particular story of political happiness lasted nearly as long as the wall’s unhappy 28-year construction. Today, its photographic memory is under copyright.

Dina Gusejnova lectures in Modern European History at Queen Mary, University of London and is Honorary Research Associate, UCL’s Centre for Transnational History, where she is on the committee of an interdisciplinary research project on Passions and Politics d.gusejnova@ucl.ac.uk or d.gusejnova@qmul.ac.uk.