Senate House recently hosted a multi-disciplinary conference exploring the role libraries have played in restricting access to published works and archival materials deemed ‘erotic’. In this post, research librarian Richard Espley reflects on the irreconcilable demands often placed on libraries.

During the recent Forbidden Access conference organised by the Institute of English Studies, libraries were portrayed as repressive organisations, concealing erotic works. In other words, exercising censorship.

Examples highlighted included the British Library’s Private Case, the enfer of France’s national collection where access is granted only after readers have negotiated a series of obstacles. At one time this was also true for Senate House Library’s Craig collection.

It is true that the absence of publicly accessible catalogues, the refusal of reprographic permission and close observation of behaviour while reading and the compulsory interviews to establish readers’ intentions, all carry a tacit and discouraging accusation of the unseemly.

However, while this is clearly a restriction on intellectual freedom, I want to suggest that it often represents a library’s pragmatic response to the irreconcilable demands placed upon it. And that the real confusion over how to define and handle the obscene, lies outside the shelves and the control of the librarian. Indeed, in such circumstances, attempting to collect these works at all, reflects a fundamental desire to preserve both the books and their discussion.

A harrowing tale of sexual abuse rather than an erotic work

As the University planned and completed its move to Bloomsbury, libraries had much to fear in their handling of obscene books. One notable case, from 1931, involved the librarian of a small public library in Manchester receiving a court summons for aiding and abetting an obscene libel, for holding a copy of James Hanley’s novel, Boy. A harrowing tale of sexual abuse rather than an erotic work, Hanley’s book had been on sale openly in the UK for more than four years without attracting the attention of the authorities.

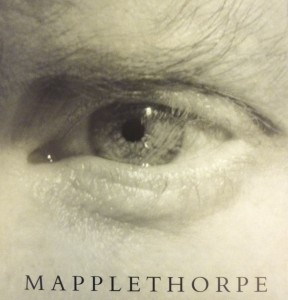

Similarly, in 1997, the police raided the library of the University of Central England, and confiscated a copy of a collection of Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs, of which 6,000 copies had been sold unimpeded in the UK. This raid was triggered by the library giving permission to a student to photograph an image, which alarmed the developer. In both cases, existing legal restrictions were no valid guide for librarians, and the imposition of elaborate special access conditions on these works would almost certainly have avoided official attention.

However, while such attempts to control transgressive works are clearly unwelcome and restrictive, it is important to note that the librarians who impose them are the same professionals who boldly chose to acquire these books. This simultaneous collection and concealment is a paradox which is arguably best explained as a response to society’s confused attitude to the erotic.

Our wider culture has been, and still is, hesitant about the absolute definition and value of either obscenity or freedom of expression; some material remains legally and culturally beyond tolerance, as it always has. Libraries, including Senate House Library, navigated this dilemma by ostentatiously restricting some material, surrounding it with ritualistic controls. In doing so, they both served and perpetuated a cultural uncertainty, which shows no sign of receding.

Richard Espley is a research librarian in Senate House Library. This blog post reflects his ongoing research interest in censorship, with an article on Senate House Library’s handling of the Craig collection appearing in a forthcoming volume in Brill’s series, The Library of the Written Word (http://www.brill.com/publications/library-written-word). Richard is also working on the effects and motivations of governmental censorship during World War One.