By Jonathan Blaney

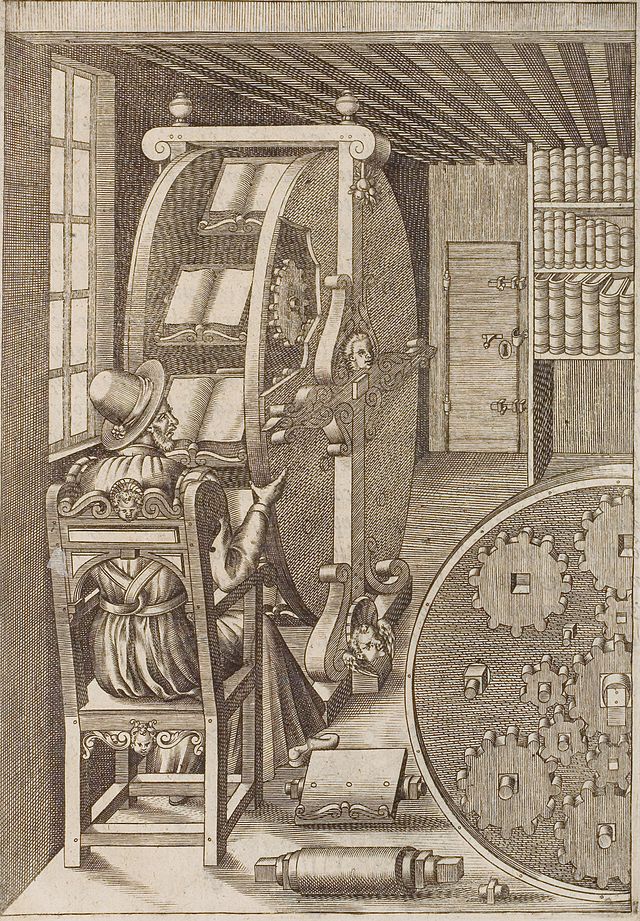

Historians have always dealt with large amounts of text and have had to develop ways of dealing with the volume of it, such as the index card or the Renaissance book wheel.

Now that much textual information comes in electronic form, that data is now much easier to access and to analyse. But some historians are under the misapprehension that text processing techniques are difficult to learn.

Many texts are now available to download in digital form. This is a great opportunity but also a challenge to the traditional humanities scholar. Those who would like to know what they can do with their text collections may not be sure where to get the information, and they may find that online courses are written for the computer scientist rather than the historian.

The IHR has written two free courses to teach historians the basics of semantic data and of data mining. No prior knowledge is needed and there are plenty of genuine historical examples to illustrate the material.

Semantic data means encoding texts according to their characteristics. The beauty of this is that the characteristics can be whatever the researcher is interested in, whether it is the date at which a placename is mentioned, the excise duty in port records, or the language used in a diplomat’s letter. If you decide that encoding the texts yourself is too much work, knowing how it is done will not only help you use other digital collections more expertly, it may even allow you to ask questions of the data that you did not know could be answered. Many marked-up collections of texts are available and free to download, and with a little experience can yield all kinds of valuable information.

Text mining, by contrast, does not assume that the text is marked up. It uses programming to interrogate large collections of texts, to find syntactical and semantic patterns to deduce things about the texts. Fortunately the programming has largely been done for us: in this course we use the Natural Language Tookit, which is avalable for the free programming language, Python. Text mining is a large topic and we have only scratched the surface in our course, but we hope that some of our readers will go on to harness this very powerful tool.

In addition we have included a tools audit along with the course. Historians may not know what tools are available and this is a jargon-free introduction to some of the most common and useful. Finally we have provided some case studies to showcase what can be done with digital techniques and historical data.

Nothing in these methods of accessing texts excludes the older methods. Just as print did not displace handwriting, or writing conversation, digital text doesn’t displace the pleasures of print. Even the book wheel is still in use in historical research.