Earlier this week I spent a day researching in the Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre at Holborn Library. Now that our weekly Festival in a Box visits with people living with dementia in Camden are well underway, my aim was to find stimulus materials which—based on the narratives we are beginning to uncover—might help to prompt reminiscence among our participants, and hence feed into the narrative collage of place (of Bloomsbury, of Camden, and of London itself) that is already beginning to emerge from our research.

Aptly, this visit took place on a day of industrial action around the University which meant that my regular library was closed. The Camden Archive Centre’s opening hours have also been restricted as a direct result of funding cuts within the last two years, and, standing in the cold at 10am waiting for the library to open, the results of this were obvious.

I was struck once again by the economies of scale at play in Bloomsbury: between my own workplace and between the council-run archives. The reading rooms in the beautiful Senate House Library and the immense, almost overwhelming, British Library—both institutions at the heart of Bloomsbury and of Camden—seemed suddenly palatial. They are palatial, of course, and the comparison with this local and entirely public institution, underlines how fortunate we are, as researchers, to have access to them.

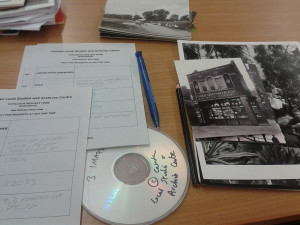

On entering the Camden archives, the first thing that you are confronted with is a table covered in boxes full of jumbled ephemera materials on sale to the general public. Here we had the 50p box, the £1 box, the box full of postcards and photographs on sale for the absurdly cheap price of 5p each.

Before delving into the archives themselves I duly dug into these jumbled and disordered boxes, rifling the contents for material to use in my own project. I dredged through these boxes looking for sources, for stories, for points of connection with the lives of the people participating in my research – people whose stories we have already begun to hear in our weekly outreach visits. And I found them, here and there amid the debris: photo stills from a theatre on St Martin’s Lane, where one of our participants had lived in her teenage years; postcards of forgotten streets and demolished buildings that our participants remember vividly.

To me, the experience of working through these materials, investigating new ways to use them as part of the Festival in a Box project, raised again the core questions underlying my research. What are the hierarchies of value that determine what is protected and what is thrown away, sold, or recycled as cultural junk? What is valued in culture, what is discarded, and how culture can be actively reconfigured to be of use to those traditionally excluded from it?

Clearly every archive and every museum needs to confront these difficult decisions on a daily basis: to make judgements of cultural value about what is preserved and protected, and what goes into jumble-sale archive of the 50p box. But it’s a question for society, too, and one that has been playing upon my mind as I listen to the narratives of people with dementia living alone in Camden….What value do we give to the dispossessed?